What asset do we have in

super abundance to trade?

India is a land of Human Capital, with 1.4 billion people, a vast majority of them in the 18 to 60 age group, but is unable to find work for them, in order to covert this humongous resource into income for these people. Why?

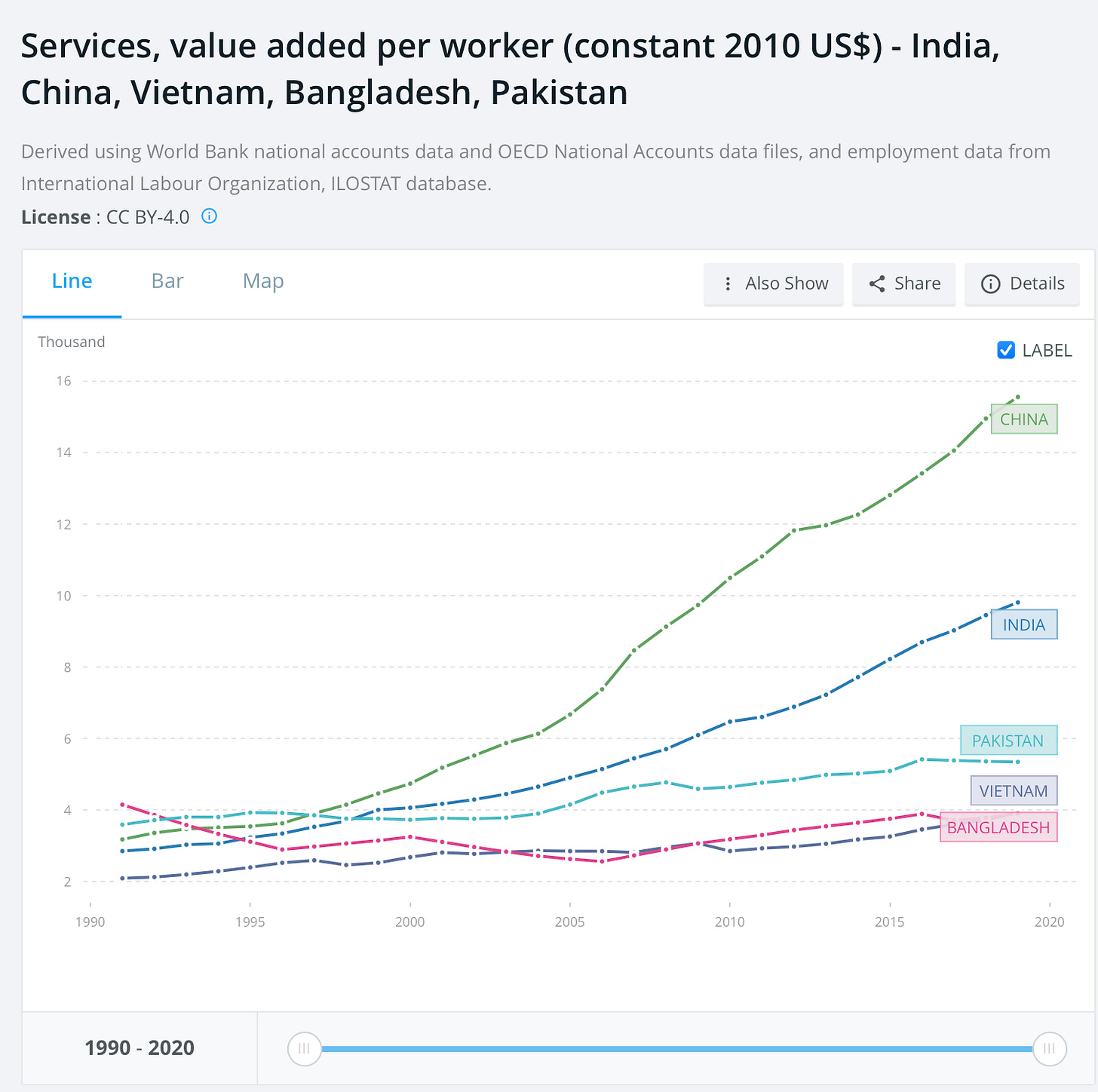

How have other countries, even populous ones like China, in similar circumstances, succeeded in effectively monetizing their surplus labor while we simply assume it can’t be done productively, and full employment requires extensive doles?

Over the decades, we have come to believe that we are an over-populated, under resourced country, with little Capital, and therefore, it is impossible to find the wherewithal to create meaningful jobs for all our people.

So we have built an economy, under an assumption of scarcity of capital, that functions like a giant vacuum machine, sucking out income from the hands of the lower half of the income pyramid, [mainly from farmers, but also consumers, by using techniques perfected by Stalin] that constituted 70% of the population, in order to funnel it to “industry,” [read favored tycoons] who it is believed, will one day modernize India, and create jobs for all.

This model has wide support from the educated elites who benefit from jobs created in high wage islands by industrialization. So a happy consensus between politicians, tycoons and the urban elites backs this model of modernization since independence.

But this “industry” cannot create all the jobs required, because it is capital intensive, and seeks to serve existing demand at home, that too of the creamy layer, which in turn is constrained, because not all people have incomes to spend, for lack of jobs.

So this vicious circle of a capital intensive industry, not investing enough to create more jobs, that put incomes in the hands of people to spend, that in turn creates more demand for industry to grown on, needs to be disrupted. Labour participation in India is abysmally low, being a notch above 50% of the total population. In contrast, our competitors like Vietnam have 80% labour participation.

The answer to this conundrum is not shunning capital intensive industry, - we need it as much as others do - but to prevent it from using its monopolistic power to extract rents from the rest of the players in any given industry.

For example, if you permit a monopoly in synthetic yarns, or Viscose Fibers, it is but natural that such monopolies will use their power to extract more than their fair share of profits from weavers, composite mills, garment manufacturers etc. This may benefit the monopolist, but overall, the textile industry, and in particular exports, perform poorly as result, because exporters are deprived of the margins needed to build brands and market access abroad. Something I hope will become clearer as you read this essay.

Over the decades, despite humongous capital sucked out of farmers through monopsony on their produce, or restrictions on their ability to monetize land, - and funneled into industry; - new job creation has been dismal, as industry remained fixated on rent seeking using “cheap and state subsidized capital.”

Note here that all incentives & subsidies to corporates have always been linked to Capital invested in a firm making gold platting of investments, and asset gathering, a very lucrative business by itself.

The number one problem in our Nation of 1.4 billion is to convert the labor of unemployed people into income for them from productive enterprises.

The key to our prosperity is first and foremost monetization our surplus labour in the global market. Labor is a highly perishable asset. If not used on any single day, it is lost for ever. If monetized it becomes capital. The rest will fall into place if we can monetize surplus labor.

That should be our national priority over-riding all else. Monetizing our labor can lead us to the goal of 10% plus GDP growth that we need to catch up with the world.

The question is how it can be done.

Monetizing Labor through

products and services:

What/which commodity, or product, - and the labor mingled in them, - you can monetize in the global market, given a certain standard of quality, is purely a function of price. The lower your price, the more you sell at that price. Let us examine textiles as an example.

In textiles - cloth or garments, - where we have a competitive advantage because of raw material availability, and the surplus [note surplus as in “unutilized" labour and not “cheap”] labour, and technology to convert cotton into cloth and garments, we should be able to outsell any other global competitor.

Yet textiles, all told, constitute only 12% of our exports, and less than 3% of global trade in them. We are unable to sell more in practice. What goes wrong?

Understanding internal

conflicts & political

dysfunction:

Suppose we had only one producer in garments, who grew cotton, spun yarn from it, wove it into cloth, and then stitched garments, say shirts, and sold them in the global market.

When selling the shirt globally, he would be looking at his total cost of production of a shirt, from cotton, to spinning, to weaving & stitching ..; and as long the selling price was more than his variable cost of production, he would keep selling shirts till he had completely exhausted either his capacity, or global demand.

His profits depend on average selling price minus average total cost, while the numbers he produces depends on selling price minus variable cost, till he is completely exhausted, or contribution from marginal sale drops to zero.

However, the situation becomes very complicated when farmers grow cotton, spinners are capital intensive mills, weavers are a mix of labour intensive handlooms and capital intensive composite mills, and garment makers are small exporters, running small factories, often just sweat shops, and with no capital to build brands or sustain market access, facing the toughest global market.

Why?

Conflict of interest. Farmers want maximum price for cotton, and politicians will often favor farmers close to elections, but mills thereafter.

Handloom weavers are very complicated tiny firms, owned and operated by minority community entrepreneurs, who want cheap yarn from spinners, and are often geographically concentrated in minority communities.

Spinners are a law unto themselves because being very capital intensive, they want to lock in cotton at the cheapest possible price.

Composite mills use yarn from cotton, but also make their own from synthetics, and want maximum price for their blends.

Garment manufacturers want the cheapest cloth, and as far as exports go, they are 2 bit players, but the only ones who know the overseas markets.

The biggest players, the composite mills are clue less about exports and know a little only about highly commoditized products like denim, or towels, or bedsheets.

Note the rent seeking incentives in all this.

Big tycoons concentrate on rentier and least competitive part of the market - petrochemicals making synthetic yarn, - and the smallest players, with no capital, face the fiercely competitive global market, with no branding power, and are price takers on the raw material as well as the finished goods side. They face the highest risk while near monopolies enjoy Govt. guaranteed rent.

So you have this medley of conflicting economic interests, nobody wants to let the invisible hand of the market sort out the problems, politicians weigh in with price/duty intervention at each stage, and reconciliation of conflicts becomes very complex and expensive.

Worse, the weakest players in the chain - garment exporters - are facing the global markets where you need to build brands with enormous amounts of Capital.

Nothing could be more dysfunctional, and note that at the core of this seething mass of conflict, is our fetish for subsidizing industry or capital, at the expense of farmers and consumers, in the belief that “industrialization” creates jobs.

Make Capital cheap and you will have jobs, has been the leitmotif running through our industrial policy. The fetish has found its master exponent under Modi. . The truth is when you subsidize capital, it cornered by the powerful, who use it to extract rents from the industry, create some high wage islands for the elites, but the industry as a whole suffers higher costs, and lower competitiveness, due to their rent extraction.

Now think the equation we referred to at the beginning. If there were no conflict of interests, we would go on using all of our surplus unutilized labor to make shirts until we ran out of labor, or cotton or the selling price of shirts fell below the cost of our cotton + labor [variable costs].

But we don’t do that because the big fish capture all the possible profits in the industry as rents to their capital intensive ventures, reducing margins for exporters to the barest minimum, as result of which exporters stop exporting long before their marginal costs, but for rent capture, equal global selling price. Rent extraction by the big fish limits exports. It is as simple as that.

Moral of the story. Our fetish with guaranteed returns to capital to the tycoons reduces the pool of profits available to those at the exporting end, reducing our potential exports.

In short we are very ineptly organized to export even where we have competitive advantage. The advantage is frittered away by our dysfunctional politics and rent seeking players. This lopsided incentives against exports extend across sectors like engineering, [where steel is allowed to capture a large pool of profits as rents through tariff walls], cement, Aluminum, etc.

Further note, these opportunities for rent seeking are created by Govt. intervention. At the top of rent creating mechanisms, and the most powerful and least visible one, is the over-valued INR.

This device sucks out potential profits from farmers and funnels them to industry. Why? Farmers use labour, land, water, sunshine all priced in INR [except fertilizers] and when they export, they earn Dollars. But by keeping Dollars cheap, and INR expensive, they are burdened with cost of subsidized Dollars given to industry. And some high end consumers.

Following this profit sucking device are a variety of other things like protectionist tariff walls, import duties on consumer goods, explicit subsidies disguised as incentives, and guaranteed post-tax return on net worth - a champion creator of rents in the oil sector into which the mother of all monopolist is plugged; - all these serve the same purpose - create rents for the biggest and the most powerful players.

These rents in turn are payed by those without bargaining and/or pricing power, and other small players in the value chain. It is not an accident that all are importers are huge industrial conglomerates and almost all exporters are downstream 2 bit opportunistic small players. [Except for SSEs as below.]

That is why we export so little - the incentives are all wrong, and skewed against exports, and exporters; and because we export so little, we cannot monetize surplus labour in order to breakout of the low unemployment malthusian trap that pins down our disguised unemployed on farms.

Why are SSEs such

successful exporters?:

Why are our software services exports [SSEs for short] so successful? Ask anybody, and the answer is “labor arbitrage.” Salaries in India are lower than overseas, we can compete effectively. Right? WRONG!!

Well, the cost of labour is even cheaper in textiles, yet we do very poorly on exports. Why are SSEs competitive but textiles are not?

From the growing cotton, to stitching garments, the labour component in growing & ginning cotton, spinning yarn, weaving yarn, cutting and stitching garments, - the whole processing chain - is no less skilled-labor-intensive than that in SSEs. So why aren’t we as competitive in textiles as we are in SSEs?

Remember what I said if there was only one firm growing cotton, spinning yarn, and weaving cloth, & finally stitching garments, and selling them globally? The firm would go on selling shirts till variable costs = selling price.

Now think SSEs. Notice it is just one firm recruiting people, training people, find jobs overseas, and then executing the contract. From start to finish, unlike textiles, the whole thing happens within one firm. There are no conflict of interests to resolves, no rent capture through political bribes, and pure economics is in play. As long as contract pays for labor and related overheads, the firm will execute the contract, subject only to management bandwidth to coordinate production delivery and customer feedback.

Where is labor arbitrage in all this? In fact, though there is such a thing called labor arbitrage, and it is important, the success of SSEs owes more to elimination of rent seeking within their value chain, rather than labor arbitrage alone.

Labor Arbitrage and

export competitiveness:

Let us try and understand labor arbitrage a little more deeply than merely as the difference in salaries paid to software engineers at home vs those paid overseas. Contrary to conventional wisdom, salary differentials are a consequence of true arbitrage, and not the cause of such arbitrage. Let us see why.

In any economy, you may classify all goods and services as “trade-able,” meaning they can be taken , as is where is, globally and sold at any given price .. laptop for example, … and “non-trade-able,” meaning there is no way to carry the good or service overseas and sell it globally - a hair cut from a barber for example. This distinction between two parts of any economy is real but blurred. In a large economy like India, and one that is insufficiently globalized, the non-trade-able part of the economy is huge; almost 70%, while the trade-able part of the economy is something like 30% or less.

The prices of non-trade-able parts of the economy are set locally by demand and supply factors, while those of trade-able parts of the economy are set by global prices. So the price of laptop in India closely tracks that of one abroad, with a duty difference of course, but the price of a haircut in Mumbai has no relationship with the price of haircut in New York.

Infrastructure is a huge part of any economy and it is something that can only be consumed locally. So it is one big chunk of the non-trade-able economy, that follows local rather than global pricing.

Let us take the basket of goods and services consumed by a software engineer in India to be 100 INR. Of this, 70 INR have prices set locally, while the balance 30 follow global prices.

Let us now double the price of the Dollar in INR. What happens to the engineer’s consumption basket?

Note 70% of her consumption is locally sourced and locally priced. By doubling the price of the Dollar, the value of this locally sourced portion of consumption basket remains unchanged. [we will ignore second order effects for now]. However, the 30% trade-able portion of the basket doubles in price, and the engineers total consumption, on doubling the price of Dollar goes to 70% + 2 x 30% = 130%.

If now we are to ensure that the engineer maintains his standard of living, we must bump up his salary from INR 100 to INR 130; an increase of 30%.

Note the magic. We doubled the price of the Dollar, but we have to increase the salary of the engineer by only 30% relative to her existing salary, to keep her as well as off as before.

The balance 70, becomes an “earning” for the economy as a whole, which is really the difference in local and global prices of the non-trade-able portion of the economy, and is something captured as “profit” by the exporter, which becomes the “incentive” for him to export more.

Do note the distinction here which lies at the heart of much confusion even among professional economists. The engineer’s salary goes up BY ONLY 30% not because we pay her less, but because the non-trade-able part of the economy, which is cheaper in INR, and represents India’s overall competitive advantage over other countries, enables us to keep the engineer as well off as before, while increasing the economy’s INR earnings by 100. Effectively, we have monetized our “non-trade-able” competitive advantage, that we could never monetize before. This injects an extra 70 INR of demand into the economy, that fuels GDP growth elsewhere.

Yes, this is sheer magic which is why it is so little understood. What have done in effect? We have taken a resource that was idle, and earned zero income, and sold it globally for $1, by dropping our price in Dollars. The extra cost we incurred in doing so was INR 30. So net net, a totally idle resource with zero income is now earning INR 70. As long as global demand exists, we can keep bringing more and more idle resources to the market till the increments earning = incremental cost.

Some have often argued but per unit of export, by devaluation, we now earn less Dollars. This argument has often stalled necessary reform but is totally spurious when you consider marginal costs. Recall that we had an idle resource earning nothing. But this resource still has to be fed, kept in good health, given a place to live etc. If you somehow convert the idle resource into incremental income, and income exceeds associated Dollar cost, you are much better off than before. So Dollars earned per unit of export are irrelevant when you have huge idle resources. Better to drop unit price and earn something, especially as labor not used perishes for ever.

This then is the source of real arbitrage between onshore and offshore costs - the fact that all of the non-trade-able part of the economy, is underpriced in relation to the global price, not just labour.

Over decades of exports, the local economy becomes more and more globalized, local prices creep up, and so costs and wages equalize onshore and offshore but not completely.

You still can’t trade highways, rail corridors, dams, bridges, nor haircuts by hairdressers.

The key thing to understand for exports, and a strategy to pursue higher exports, is that your competitive advantage comes from the value to price equation of your non-trade-able part of the economy, and not from from what you are trying to export per se. The key problem is therefore how to monetize the non-trade-able portion of the total cost of a product you export, such that it becomes a meaningful value proposition for an overseas buyer.

Note there is lots of confused thinking here on devaluation, import costs going up as a consequence, with we being a net importer and so on and so forth. All that is true but they are second order knock-on effects.

A change in value of the Dollar does not alter the 2 basic things at the core of the economy. Firstly the percentage of economy that is trade-able globally. And secondly, the value to price ratio of the local priced portion of the economy.

The change is the prices of the trade-able price of the economy alone and we can fully compensate for that, and still come out with a surplus.

It is like utilized capacity or labour. If you can’t find work, no matter how skilled you are, your earnings are zero. On the other hand if you find work, whatever you earn is an incremental surplus. Same for unutilized portion of the domestic economy. For every shirt you export, whatever you earn over above the 30% trade-able portion of costs, becomes an incremental earning for the economy. True the surplus is captured by the exporter in the first instance, but it is something “earned” by the unutilized capacity of non-trade-able portion of the economy.

So what does a devaluation of the INR really do?

When you devalue your currency what you are telling the world is that I have surplus capacity, in our case labour, plus some underutilized assets in the economy, which you are willing to sell or provide at a cheaper cost than before.

Recall my earlier essay where I said we should aim for full employment; which is to say, we must keep exporting whatever we can, for whatever price the export product will fetch, as long as the earning is greater than the variable cost of exports before labour.

There is much confusion in Reserve Bank’s model for calculating relative productivity gains between two time periods, usually 2 decades apart, that I shall explore in a later article. However, there is also much concern about “currency manipulation” that the US is supposed to fling at trading partners when they let their currency depreciate against the Dollar.

Consider for a moment that we discovered a hitherto Lithium mine in the foothills of the Himalayas in Bihar, and developed it, and began exporting it to battery manufactures abroad, bringing Lithium prices to half its current value. Could the US accuse us of manipulating Lithium prices in order to export more of the stuff? Would such a change find any support in the world?

The same argument holds good for labor. And the assets in the non-trade-able part of our economy that we should monetize through exports for full employment. We have under-utilized resources and we are within our right to bring them into full use. If full employment is laudable goal for the US economy why isn’t it so for India?

Fact is because full employment is not even our goal means we don’t make this argument abroad in places like WTO. Instead we have internalized the wrong sort of narrative that full employment is a “luxury” we can’t afford. Those abroad will only be happy to encourage us in such foolishness. It is time we shed such self-defeating narratives and formally set full employment as our national goal combined with a resolve to export anything we can till we achieve it.

In short we will sell, shirts, footwear, cereals, and software services by making our products cheaper to buy so long as we have unemployed people. Only when we reach full employment, we will stop and say no further price reductions. We have equilibrium here.

Note for readers:

This a continuing series of essays to explore and show how a per capital GDP growth 10% plus rate is feasible for India, and that such goal must be the topmost maximand of our national strategy.

The essays so far:

How China has weaponized trade against India. Read here.

Why full employment should be Number 2 goal of our National Strategy: Read here.

Understanding the Kautilyan Maximand: Read here

Three to four more essays to follow that step by step lay out my case for an export led growth strategy for India that focuses on full employment.

Mam, wonderfully written, I don't have an economics background but understood most of it. Will understand more as I read more. Power to you for sharing knowledge. And I wish those who can make changes see these articles and act on it.. looking forward for more...

Super piece. Keep writing.