Understanding the Kautilyan Maximand:

To break out of China PacMan style containment, India must grow its per capital GDP at 10% plus per annum

Understanding the Kautilyan Maximand:

Foreign policy flows out of what you want to be, and do, or achieve, as a nation. You cannot be, and do, all possible things. Given the reality of resource constraints, you have to pick and choose. Wisely.

Concealed with the range of choices you face, are often creative, but not so obvious choices, that generate resources to make more options possible. For instance educating your people well, using the virtually free human store of knowledge, creates almost unlimited new human capital, with which a nation can earn a living.

But these choices are lost on those obsessed with brick and mortar, power and pelf, of selfish existence. Elites often ignore such resource creating choices as they threaten their very own dominance of others within the nation.

However, societies such as South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, and others show, how choosing resource-creating routes to development, of which education is just one such choice, not only increases available capital, & the range of available options for growth, but also the brick & motor, power and pelf, that elites hanker for. It is a question of being creative, and making choices after deep thought, - choices that bring everybody into the development process - that makes the difference between slow GDP growth, and that of champions.

So what do we as a nation want to achieve? Slogans are not policy. A good way to begin the search for an overarching goal that anchors all policy, is to see what our ancestors did, and also to look at what is validated by others. So let’s begin with our ancestors.

Kautilya, in Arthashastra, says:

“The foremost duty of a King is to increase his wealth, [and that of his citizens], by settling virgin forests, or by conquest.”

You must of course read his wise maximand in the context of the development choices that Kings faced circa 300 BCE. In those times, agriculture, minerals, trade in cloth made up 90% of the economy. New wealth was mostly created by clearing forest for agriculture. [And sons for working the new lands.] The duty of a King was to create the options for growth of wealth, and well being of his citizens, by growing the economy.

In the modern world “conquest” or appropriation, is no longer a wise option since trade has almost fully replaced conquest. For the sake our security pundits, I will repeat that because they still haven’t got the memo. In the modern world, trade has replaced conquest as one of the means for, not only growing your wealth, but also appropriating that of others. The previous essay was to show how China is using trade to appropriate our wealth.

Kautilya’s insight, even back in 300 BCE, was sharp and deep. As you scan the National Security strategies and doctrines of modern great powers, you will find Kautilya’s maximand at the top of their agenda.

In fact, USA, UK, Germany and Japan make maximization of citizens’ wealth and well being, their top-most agenda in their National Security doctrine, while Russia puts it at number 2. [Russia privileges defense of its land-mass at number one because of its size, sparse population, and the fact that defense of the flat land-mass is only possible at certain critical choke points. If those choke points at the edges are lost, the Russian land mass, given sparse population, rapidly crumbles.]

In India, the land of Kautilya, we have no have no written national security doctrine; no one knows what the national maximand is. Written policy is foreign to the land, and foreign policy is largely about how to handle Pakistan, and/or China, and how to buy cheap weapons abroad. Trade, that has replaced conquest, in the wealth maximization matrix of options, is the least understood by our security pundits, the military experts, and our economist. Does it inform foreign policy? At best, only in speeches made by erudite EAMs at conferences.

As I will show in this essay, the Kautilyan maximand is still the most relevant one for India, and if properly understood, and applied diligently and intelligently, can lead India into 10% plus annual GDP growth, which is also the only ticket available to be a rising power of some consequence in the new global order. So let’s go back to deriving what we should be doing to meet the Kautilyan imperative.

Domestic Champion

Theory of Economic Growth:

Giving credit where credit is due, one must concede that although Modi hasn’t articulated India’s national security doctrine as a Kautilyan maximand or imperative, - he should, if only to get everybody on the same page - he is trying to follow that percept in his own way.

I am not saying Dr Manmohan Singh did not have such an objective in mind. In fact, among all the PMs, his understanding of the need to grow the economy in order to emerge as significant power was the sharpest. And he did articulate it many times; but as was his wont, - his speeches sounded more as if he were addressing a Board of Directors meeting rather than rousing the laity with enthusiasm to win support for his policy, - his articulation had little impact on laity and pundits alike.

Modi however has taken the economic growth imperative to mean that India must build up domestic business firms - or rather tycoons who own such conglomerate of firms - by giving them Govt. favors, in cash or kind, in order to help them grow in scale and size, and emerge as champions. He has also conceded that they need protection from foreign competition in domestic markets, and has therefore built rather steep tariff walls, to protect their profits, at a great cost to hapless citizens, who fork out the cash for the rents that are disguised as profits to such tycoons.

So Modi’s goal of growing the economy is right. However, will his strategy produce results that truly benefit India, and its citizens, or only the tycoons? Part of the reason for writing these essays is to explain how Modi’s strategy - of building domestic champions by conferring Govt. favors on select tycoons via stealth taxation of consumers - are suboptimal; both in terms of the GDP growth produced, but also from the perspective of growing citizens’ wealth, as opposed to that of tycoons.

-

Chaebols of South Korea, and the Toyotas of Japan - the MITI inspired growth strategy of Japan is an object lesson in what a Kautilyan inspired maximand can do for its citizens - are often cited as support for Modi’s Domestic Champion theory of growth. China too offers some such examples. So why should Modi not succeed where South Korea, Japan, and even a populous China, succeeded?

The answer lies in one word - Exports, the dreaded word in Indian business circles, and the economy. Korea’s chaebols, Japan’s Toyotas, and indeed China’s billionaires, were chosen for their ability to compete abroad in export markets; - not merely exploiting domestic markets behind high tariff walls, that extract subsidies from the hapless consumers for their growth.

All these countries chose export champions, and they rewarded such firms with cheap capital, in order to enable them to scale up in export markets. That is why they succeeded, while Modi’s Domestic Champions will neither grow beyond a certain size, nor become export champions.

Instead they will become expensive domestic monopolies - as some already are - that excel at extracting rents in sheltered markets by owning the politicians - whoever the politicians are - through anonymous electoral bonds.

I know my left & liberal friends fancy that this cosy arrangement will be disrupted under their preferred leftist regime. Far from it.

Indira Gandhi invented this model of growth under the tutelage of card-carrying communists. She called it self-reliance. Growth was to come from import substitution. Her word’s for Modi’s Make in India.

The only difference between Indira Gandhi’s model, and that of Modi, is that Indira Gandhi sold her model to the gullible laity with leftist slogans of “Gareebi Hatao”, and poverty reduction, while Modi sells his model - to virtually the same gullible laity - as robust Hindu Nationalism, while scaring them of domination by Muslims, - in a land where Hindus command an 80% majority - that is construed as more Right. The fact that it impoverishes the same gullible laity, is unlikely to bother either Modi, or the leftists who succeed them; unless we take care to understand what makes the economy tick and grows for us - the laity.

Indira Gandhi’s regime produced the poorest growth rate of any regime in our history, except the British, at 3% pa in her first stint over 12 years. Her alliance with Russian inspired communists crippled India economically. May be she had no choice given US hostility to India in those times. We have more choices now. But Modi is all set to repeat her dismal performance in his allotted 10 years. And for the same economic reasons I detail in the essay.

So Left, Right, labels are rather irrelevant. I am not at all convinced that the present Congress Party fully embraces a liberal political, and equally liberal economic, doctrine. So beware, and stick to economic fundamentals before all else.

Why do exports matter

so much to growth?

With a vast continental-size economy, the 4th largest in the world, and 1.35 billion people, - largely poor no doubt, but with then with that much more potential to grow - why does India need exports in order to grow at a decent pace?

Understanding the crucial role exports play in a developing economy like that of India, is critical to understanding how to get it to grow at a pace that transcends internal constraints on growth. Part of the reason in writing this essay is to show that:

India needs to grow it’s GDP at a minimum rate of 10% per annum, for at least the next 2 decades, to catch up with China, and regain leadership of its neighborhood - what the Vedas refers to as the “sacred land” - that may be 7 different nations today, but is one contiguous geopolitical reality, with a shared destiny, that India will inevitably shape and lead, unless it itself collapses.

Using internal dynamics alone, never mind the continental size, and 1.35 billion people, India cannot grow beyond 5% to 6% pa once the economy itself reaches full capacity utilization. [It is presently at something between 70 and 80% capacity.]. The balance of 4 to 5% percentage point growth - or virtually half of the required growth in the economy - has to come from exports.

Stagnation in growth of exports over the last decade, particularly under Modi, has tripped us up in GDP growth, and led us to lag our smaller neighbors like Bangladesh in per capita income.

Getting exports to lead growth is imperative. But as I shall show, Modi’s current policies are diminishing growth in exports, and over time, protectionism, combined with China’s moves to impoverish us, & will eliminate us as a potential a competitor in Asia, and the globe.

Such policies will cripple exports and restrict India to the lower trajectory of 4 to 6% annual growth, that can never enable India to catch up with China in power, reach, and influence; much less in per capita prosperity of our citizens.

Let’s understand GDP, exports, and the growth

dynamic a bit:

I will layout the story in easy to understand, and assimilate, graphs. These graphs, especially longterm, carry the distortion that the basis of the calculation is often changed - such as GDP, inflation, or even some kinds of exchange rate indices, - and as such are not “continuous” graphs but those with discontinuities.

Therefore, the decade to decade comparisons can be misleading unless one notes the discontinuities. But for all that, the story that the graphs tell is authentic, the direction impeccable, even if the scale is slightly distorted. You will not draw wrong conclusions from the graph as presented if one sticks to the context in which they are presented. So let’s take a look at them. [I shall mark the discontinuous graph from those that suffer from no such distortion.]

Here is the story in graphs:

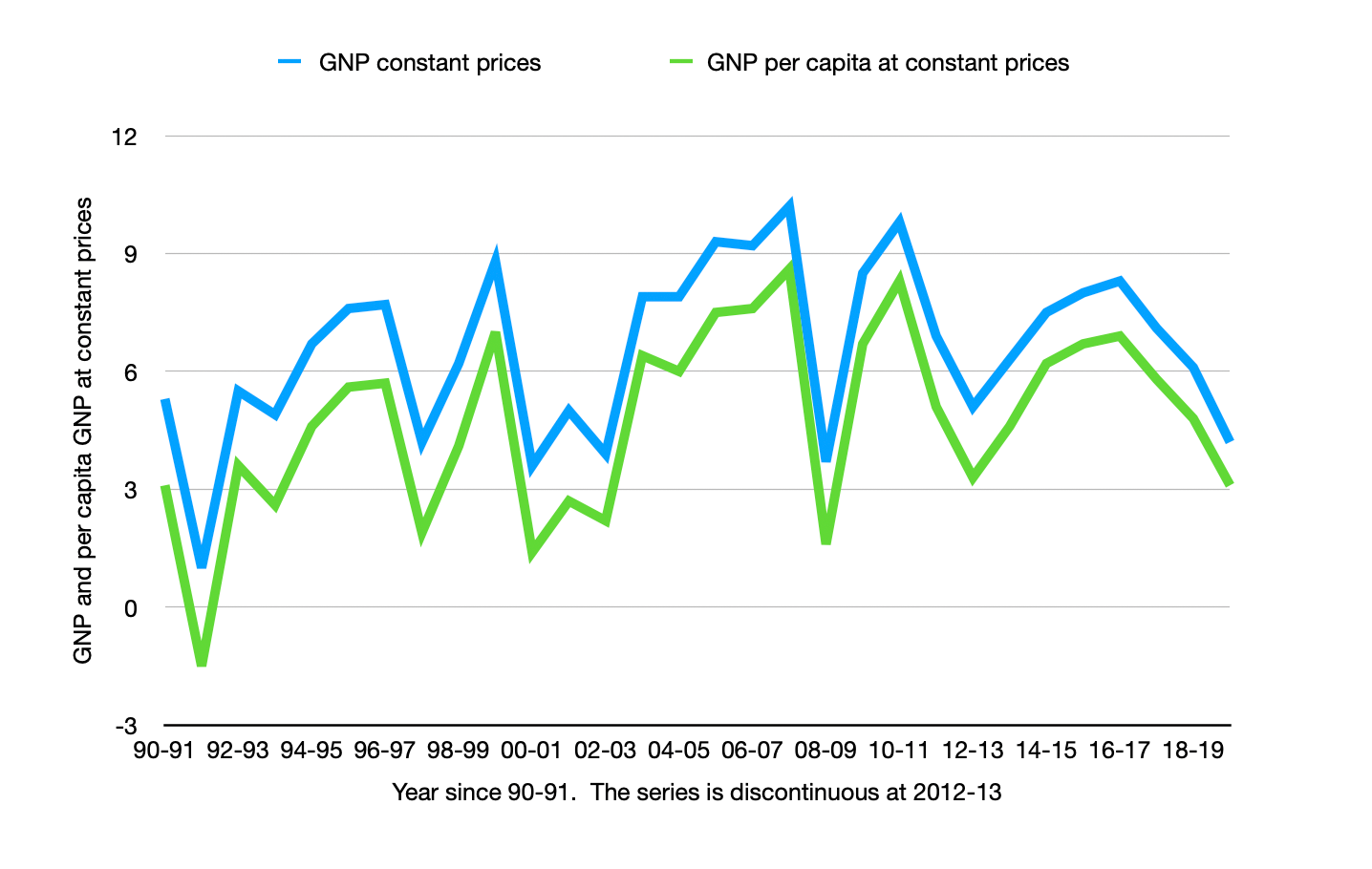

First the annual GDP growth in Trillion INR per 201-12 constant prices. But the data suffers from discontinuities and is presented here only for perspective.

And here be exports as a percentage of the said GDP series.

Exports lead the GDP growth nicely after the reforms of 90/91. Both GDP, and exports as percentage GDP trended upwards in step.

Then since 2012-13, the exports as a percentage of GDP started wobbling, and tanked inexplicably after 2014, when Modi began to work his protectionist magic on the economy, first through tariff walls of import duties on commodities, and secondly, through a “strong” INR that somehow is falsely associated with robust Hindu Nationalism.

Trump too rode to power on the back of a faux nationalism that celebrates a “strong” Dollar. Trump was quickly persuaded by economic logic that a “strong” Dollar hurts the US economy. But Modi and his Bhakts continue to be impervious to economic logic.

As percentage of exports to GDP started to wobble and decline, so did the GDP growth rate. Below are GDP growth rates since 2011-12 and the corresponding exports as percentage of GDP that show the trend reversal.

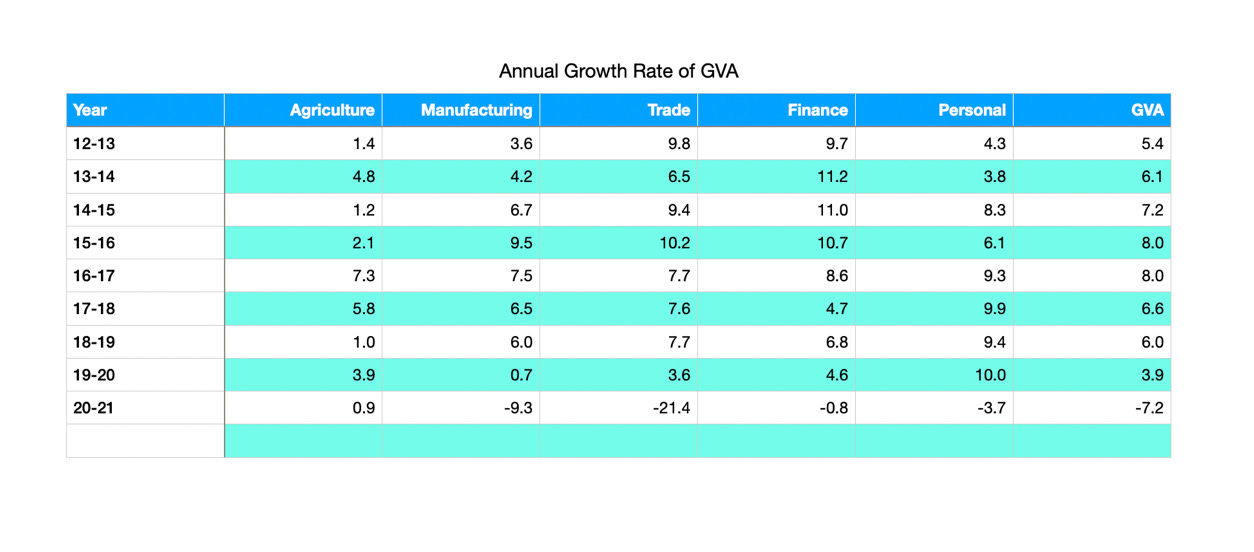

The growth rate in GVA from 2012-13 onwards, till data is available.

In absolute terms the picture is even worse showing almost zero growth in exports over last 7 years.

As exports tank, the rate of growth of GDP falls dramatically trending back to the maximum that is possible, given the internal domestic savings rate [DSR] of the economy, and the Gross Capital formation [GCF]. You can escape the upper band of the internal constraints only through tapping external savings and with exports to service them. To understand these, let us examine, first the components of growth on the demand side and then the constraints imposed by the savings rate and Gross Capital formation.

Understanding growth by

origin; that is to say,

broad sectors:

Here be the annual growth rates by sector. To avoid crowding, I have disaggregated the graphs for clarity. The other sectors follow.

First note GDP has dropped off from a growth rate of 8% plus in the 2004-2014 decade to below 5% pa, even before the pandemic.

The growth rates for years 15-16 and 16-17, demonetization was in late 2016, are clearly manipulated, first by a change in basis of calculation/base year change, and second by sheer skullduggery. For proof, look at the following table taken from the Economic Survey 2021.

Somebody forgot to, or found it impossible to, fudge the export import database in the Reserve Bank. If you look at the series in the 30 year persecutive, never have export-import numbers been so out-of-whack with GDP growth as in the years 2015-2017, when Modi tried to massage the data to show growth under him was higher than in the previous decade.

Be that as it may, we can see, on one hand, the share of financial industry rising in the overall GVA, while that of manufacturing has been falling, and has never recovered from the shock of demonetization, due to which thousands of tiny firms went belly up, never to return to business.

The resilience shown by finance is discomfiting. In the first 3 years of Modi, it basically reflects the non-recognition of NPAs that were carried on bank books, inflating the value of bank assets and the GVA for that period. The NPAs caused by the pandemic shock have similarly not been recognized in the system. This is reflected in the Finance showing zero growth in 20-21, whereas the rest of the economy tanked by 7.3%. Fair to say the quality of the data is highly questionable. What is noteworthy is that manufacturing provides about half the jobs in the organized sector of the economy and nearly 60% in the unorganized sector. And this sector of the economy is sinking for the past 2 decades.

There is a systematic bias towards “financialization” of the economy since 90/91 reforms. This was largely due to mortgage finance being taken out of the ambit of employers, who use to finance housing for employees, into a separate mortgage finance industry. It also reflects the broad and welcome trend of households using financial instruments for savings. However, IBC has not prevented larceny of funds from the banking system, whose losses are financed by RBI through stealth taxation of bank depositors by keeping loan spreads very high in the range of 450 bps in real terms. Such fat banking spreads are unheard of in global markets. This distortion results in the profitability of the financial sector being 3X times that in manufacturing. [in terms of net owned funds]. This further distorts the incentives for job creation away from manufacturing as finance is relatively less labour intensive now, thanks to technology.

Next take a look at the contribution to the GVA from these sectors, again for a perspective on the lopsided structure of the economy that we are creating.

Here is the share of finance in GVA over the years:

Note the spike in share of finance in total GVA in 2021. That’s because of non-recognition of bad debts triggered by the shock of the unplanned economic shutdown ushered in by Modi by banging of thallis, and lighting of diyas. Sooner or later they will be accounted for, but nobody will adjust the over-stated GDP caused by unaccounted bad debts.

Here is manufacturing:

What is left to say? Given Modi’s protectionism, the inefficient sectors of the economy will reap windfall profits, while the competitive sectors of the economy that export their output will suffer. Take the 2 and 3 wheelers manufacturers who enjoy a large export market. As deep-drawing sheet metal prices go up due to high tariff walls, steel majors are busy raking in high margins of profit, while raw material prices for auto-manufacturers go through the roof. The net effect is that the auto-industry, that adds more value in the economy, and employs more people, will suffer shrinking export profits, while resource intensive, inefficient steel producers, enjoy a bonanza. They have been raising prices even as demand shrinks. Such is the sheer perversity of Modi’s Domestic Champion theory of growth. But more on that later.

Services have continued to grow modestly under Modi’s Domestic Champion doctrine of growth largely because he has left them untouched. The one sector here, that was responsible for the high growth rates of the previous decade was real estate. This was largely due to urbanization around small towns that converted agricultural land for urban use. This unleashed huge amount of monetary demand in the economy, some times as high as 20 to 30X the book value of the property, that fueled consumption demand, and also some inevitable inflation. Modi shut down this urbanization with RERA, and the sector tanked, as did associated urbanization. REERA was good, but you need reforms without disrupting markets needlessly. I don’t think growth will return to the sector in the near future. Another unintended casualty of Modinomics.

And lastly, here is Modi’s glorious “small Government” that he so promised to usher in:

In keeping with the general genius for perversity of Modinomics, the “small Government” is the only sector that continues to “grow” largely because its “growth” is a drain or expense, rather than an earning. It continues to grow because it uses the sovereign danda to finance itself. As a result, combined Govt. debt has now touched 90% of GDP, and RBI is generously working the printing presses to create money out of thing air to keep Modi’s “small Govt.” growing, even has he tries to dress his subterfuge in Center state “bhagidari,” to steal from states’ share of revenues, such as those from excise on petroleum products.

Meanwhile, Modi diverts all the Govt. spending on 4 and 6 lane highways for showing off “development” while feeder roads from villages to state & central highways suffer neglect. This does little to integrate villages and small towns to the larger economy that would greatly enhance rural productivity. Modi prefers bullet trains and central vistas over productivity enhancing rural roads & and rural housing that would create a lot more jobs and incremental consumption. But you are an anti-national urban Naxalite if you point to this simple return on Investment criteria of public spending. What India needs desperately is value-for-money productivity. What we get is Narmada waterfront & Central Vistas when it is not statutes and Mandirs for more prayers to the Gods for divine prosperity.

Overall, Modi lacks a vision for growth that focusses uniquely on abysmal Indian productivity in agriculture, manufacturing and services. We invest huge numbers in basic things like railways, but will not build the needed over-bridges and transit ways needed to step up productivity of ordinary users of the system. The same lack of consciousness of “delivered” productivity dogs all systems. We don’t measure end results.

Meanwhile, Agriculture saved the day for Modi during demonetization and the pandemic shocks:

In keeping with his genius for perversity, Modi has declared war on farmers just as agricultural commodity cycle turns up globally, after two decades of a deep bear market. Not surprisingly, the agenda was to hand over wholesale and retail trading in commodities - cereals, but also sugar, cotton, tobacco - to tycoons and wait for the bonanza in bullish global markets. Farmers are resisting what Modi calls “reforms.”

As you can see, it is the only sector doing relatively well, thanks to export markets and generous subsidies for sugar exporters just before markets turned bullish. Exquisite timing. Even traders don’t cut it as fine as the babus who set Indians import-export regimen. Who says babus don’t understand markets? It all depends on which side their bread is buttered.

A brief survey of all sectors of the economy by origin of industry reveals no hidden treasures that can be unleashed to produced economic growth, except monetization of agricultural land. But with Modi at war with farmers, and given his lack of understanding of land-use reforms, such monetization to add 2 to 3 percentage points per annum to India’s GDP growth, that China used to win rural support for its economic reforms, must remain a distant dream.

Modi tried to pass on the undervalued farming land to tycoons in his term but was thwarted. He is unlikely to command the kind of trust required from farmers to attempt land-use reforms. Do note, that Modi could have offered to free agricultural land, from price & use controls, in return for ending subsidies, but such is greed, that Modi expected farmers to let go of INR 2 trillion in income just to be happy “nationalists.”

What about the Savings, GCF,

FDI, value-chain investment

dynamic?

Having seen no light on the GVA by origin scenario, can stuff like assembling cell phones with imported chips do the trick of setting off some economic growth?

Let us look at the gross domestic savings [this includes significant dollops of FPI + FDI as well, though not what comes in incrementally,]

Gross Capital Formation or investment in the economy together with consumption by consumers and Govt.

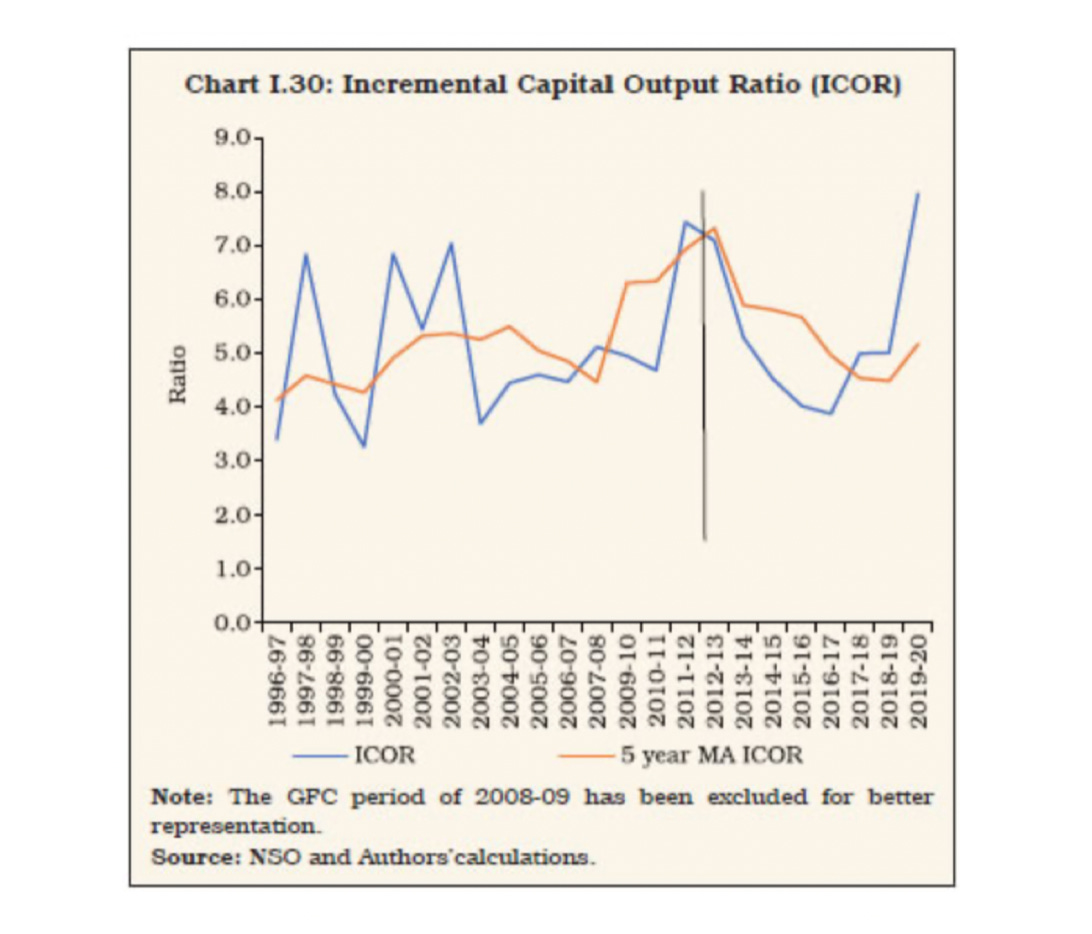

We also take a look at what growth a unit of additional investment produces the economy, the so called Incremental Capital output Ratio or ICOR, to estimate what can be done with existing resources in the system. I will try and keep it as common-sensical as possible, & without confusing jargon.

First the Domestic Savings

Scenario:

Very little survives Modinomics. As you can see, Gross savings in the economy [GDS: total] have declined from 34.6% in 2011-12 to 30.1% in 2018-19. Later numbers aren’t available but will surely have tanked further below 30% of GDP.

Correspondingly, the total investment rate, private sector plus Govt. or public sector, has tanked from 34.3% of GDP to 29%.

Since 17-18, Modi has tried to crank up public sector investment - lots of money going into bullet train and 6 lane highways and metros - in order to step up growth, with little result. Metros is a very productivity enhancing service but the same isn’t true of 6 lane highways despite their good looks that invites jets landing on them.

This has cranked up Govt. debt but produced little growth. Worse, combined Govt. debt having ballooned from 67% of GDP, to 90%. Govt. is credit 1 notch above junk in global markets.

Taking all these factors together, Modi has hit the end of the road to using public debt to finance the splurge on 6 lane highways for the Hindutva hinterland. Luckily Modi hasn’t added to the bullet trains on order for diamond polishers from Ahmedabad to save on fees paid to Angrias.

Within the overall savings investment scenario lie many disquieting trends that will hamper future growth as availability of debt becomes an overriding constraint on investment.

Here is the graph of household savings, private sector savings, which are actually plowed back profits, and private and public sector investments. [Don’t be fooled by “public sector investments.” More often than not this is printed money sloughed into 6 lane highways & nothing else.]

The graph looks cluttered but is very simple to read. The red line is the total investment in the economy, both by the private sector and Govt. This is called Gross Capital formation, and represents new investments made in the economy. We will call it GCF here.

If ICOR, is 5, each unit of GCF produces 1/5 or 20% incremental output 0r 1% growth in GDP in subsequent years. So if GCF is 30% of existing GDP, it will produce a 6% GDP growth [one fifth of 30% GDP] in subsequent years.

Since GCF captures all of the investments in the economy - domestic plus those coming from FPI + FDI, - this is the maximum rate that the economy can at provided it is operating at full capacity. This is the economy’s alpha component of the growth rate.

The Beta comes from changes in capacity utilization, and can be negative or positive. The total growth is alpha plus/minus Beta. Here we are concerned only with Alpha. That the longterm potential growth given an ICOR of 5. [ICOR itself is a wild animal that zooms from 3 to 7 in any given year. Here I am assuming 5 because that is the 5 year moving average of ICOR estimated by an RBI paper published recently. [The graph shown above is from the said RBI paper.]

And so remember this take away. In the best of existing worlds, India’s alpha, given ICOR of 5, and savings rate of 30%, is 6% pa annum.

There is not a chance that we can better that rate under the present policy regime. Given the inefficiencies of the system and the recurrent exogenous shocks that reduce alpha, my guess would be that we can grow on our own steam, with current level of borrowings from abroad, [that’s FPI, FDI, NRI deposits and net loans from abroad] at no more than 5 to 6% per annum max. There isn’t a snowball’s chance in hell of our catching up with China under the present policy regime.

Is the Govt. solvent

with an alpha of 6% pa?

The question is, even if we assume that we desire no more than 6% growth per annum under the present policy regime, is the Govt. solvent enough to carry on at this rate of growth indefinitely? Or can the Govt. be pushed into bankruptcy by a ruthless China using nothing more than a fe more adverse trade moves?

To understand this conundrum let us look at the savings, investment scenario in a wee bit more detail. The following table will help.

Household savings, has been trending down for over 2 decades, and is currently at 19% of the economy. [I am taking a median number, and not the pandemic induced crisis number.]. Of this about 60% is in bank deposits, mutual funds and other financial instruments that flow into the economy, and are available as source of investable funds to private sector & Govt. The balance 40% are fixed assets like Gold and real estate, that represent end use, & are no longer in circulation. So, households provide, 11.4% of GDP as money for investment to the private sector and Govt.

The private corporate sector “saves” [its plowed-back profits plus depreciation etc] another 11% of GDP, while it invests about 21% of GDP. So it needs to borrow about 11% of GDP to able to invest what it takes to produce a 6% GDP growth rate. Household savings being 11.4% of GDP, all of household savings are already fully exhausted by private sector demand.

What of the public sector and/or Govt.? As you can see from the table, the Govt. “saves” about 1.5% of the GDP and claims to “invest” 7% of GDP. [The claimed “investment” of 7% of GDP is bogus as it includes borrowings to pay everything from babu salaries, interest on Govt., debt, and even subsidies to corporates and the poor. The investment is fiction except for 2 to 3% of GDP on infrastructure, but borrowing is real.] So Govt. needs to borrow at least 5.5 to 6% of GDP in a market where there are no surplus financial saving to be had. You could say that the 40% household savings in physical assets could be monetized, but then why should households borrow against those assets to lend to the Govt. at a rate far lower than the cost of their borrowing?

The long and short of it, is that even the 6% alpha that we calculated here is unsustainable at the current rate of gross savings of 30% of GDP. If nothing were done, even a continuation of existing policies, would only see alpha fall back to the 3 to 4% old Hindu rate of growth under Indira Gandhi. The future under the current policy regime is very bleak.

So why doesn’t Modi’s Domestic

Champion theory of Economic

Growth not help us to grow

faster?

On the so called economic right of the Indian polity, [there only handful of such people lead by thinkers like my favorite Editor ji] who believe “robber-baron brand of capitalism”, produces the initial dollops of Capital needed to grow rapidly. This myth refuses to die even the face of modern macro-economics, where the gross domestic savings number captures all the savings produced in the economy from which comes the Capital for investment. The robber-barons don’t produce additional savings over and above this number out of thin air for investment.

Modi on the other hand, has revived the traditional King-merchant alliance that has prevailed over the past centuries. In this model, political-and economic power combine, to create a large pool of cheap labor at the bottom of the income pyramid, [that was the economic function of the caste system, and still is,] to enable the elites to live in relative luxury, even as the gullible chase their mythical karma by following their delusional dharma.

Be that as it may, the first thing to note is that domestic champions bring no additionally to the savings rate of 30%. That pool of savings includes everything that can be saved. They only borrow from it. Or preempt savings coming from abroad as Reliance recently did, grabbing what was earlier destined for a standalone refinery in a joint venture with KSA. So champions or not, the alpha cap of 6% remains, even if the Govt. stays solvent, which it cannot.

So what is the fatal attraction of the Domestic Champion model? Especially for right wing politicians and their hangers on.

Remember if you are a favored Adani or Ambani, or X or Y, Govt. favors mean you grow at the expense of others. So while savings may remain 30% of GDP, ICOR at 5, and alpha at 6%, your share of the 30% of savings grows much faster than that of your competitors, and therefore, you possible alpha is much higher than 6%.

You grow much much faster than the rest of your competition, and so long as the favors keep coming, a portion can be safely & profitably be employed to keep your favorite politician in power through anonymous electoral bonds. What used to be good old corruption, becomes a legitimate social norm of producing an orderly society by contributing election funds to a political party. The nub that P B Mehta called “structural corruption.”

That is the true nature of the Kautilyan King-Merchant alliance which used to put prominent merchants as nobles in the Kings innermost privy council. But as I said, argue, any which way you want, domestic champions produce incremental growth only for themselves, at the expense of their competitors, but bring no additionally to Alpha for the economy as a whole, which alone determines whether you will catch up with China or not.

So under what circumstances, or mix of policies can domestic champions contribute to alpha in order to beat the 6% per annum imperative?

This can happen only when the domestic champions become world champions and start exporting an incremental 40% of their total output on a net basis [meaning their exports minus imports should be at least 40% of their turnover]. But curiously enough none of the chosen merchants is a significant exporter on a net basis; not even Reliance when you deduct the cost of imported crude from its diesel & petrol exports to arrive at net exports.

And remember the GDP equation. Only net exports contribute to GDP. This isn’t coincidence. A net exporter, and global champion at that, would need no favors from the Govt. They could dictate their terms of engagement. So merchants craving Govt. favors don’t usually have significant exports. That’s why the exporting community doesn’t line up to donate to anonymous electoral bonds. Having finally drifted to a discussion of exports, let use examine how exports can help beat the 6% Alpha ceiling that the given level of 30% of GDP savings impose on us.

How do exports help beat

the ceiling of 6% on Alpha?

I promised I wouldn’t get technical. But what I am about to say is really just commonsense. So let me give a simple form of the GDP equation which is this:

GDP = C + G + I + X;

Where,

C = Consumption expenditure by all except Govt.,

G = All money spent by Govt. on salaries wages, net interest payments;

I = all investments, which is our good friend GCF we met earlier; and,

X = Exports out of the country - imports into the country.

Exports out the country are unconstrained by domestic demand, which is the total of C + G + I. Exports depend only global demand. They can grow without limits set by domestic determinants of demand. That’s the beauty of export led growth. It breaks free of internal demand dynamics, and doesn’t require frequent “stimulus” packages like domestics do.

But hang on. Don’t exports require building up of production capacities, which means somebody has to invest in them as part of GCF, which in turn means the investment must come out existing pool of domestic savings of 30% of GDP, which means we are simply back to the same ICOR of 5 and alpha of 6% ??

You are absolutely right except for once factor. To create capacities for exports, you can borrow from the deep pool of global savings that have virtually no limits. The only constraint here is you must export most of what you create capacities for, and you must have a something to export in a form the world needs. So through export led growth, like say software services, you can grow without any constraints coming from the internal demand side, as also from lack of savings because you can borrow without limit from abroad. PROVIDED you have a robust exports lined up.

India’s main weakness since independence has been the inability to export, and build a culture and capacity for exporting. All successful global champions, on the other hand, even the fastest growing neighbor Bangladesh, were created by building capacities for exports. If Bangladesh beats us today on per capita income, or Pakistan does so a few years from now, it will be on the back of their exports, in products and markets where India has excellent competitive strengths; but which lie fallow because we are chasing the false Gods of glorious Hindu Nationalism, whose INR needs to be as strong as Bhima so that our elites can pretend they also run a super-power.

Let’s now understand, What we can export

and how.

Fixated in our minds is Alandi, and the idea of how cheap labour can be used for exports, and how it can be used, - to break ships - and earn foreign exchange, which is the same as exports. This is a rather stupid way of looking at the whole idea of exporting our biggest asset - labour.

To understand our competitive advantage in its proper perspective, we need to break free from this mental model, and see any product as a product of labour, if it uses labour that constitutes more than 10% of its total cost of production. Our labour, all told, costs less than half its global value, and 10% input means a competing Indian product, for a given quality, is already 5% cheaper than its global counter-part. And 5% of selling price is a very decent competitive edge.

Viewed in this wider context, everything from rice to rye to corn to soya becomes an export product that essentially exports labor. Only the “for” varies according to what is in demand. [The importance of this will become obvious when I discuss how to price labour ignorer to make the world use our labour in preference to that of our competitors without reducing local wages]. This includes, the whole gamut of industries like textiles - from cotton, to yarn to fabric that constitute 20% of our total exports. [Agricultural commodities are another 20% of our export basket. Software services at about $130 billion constitute about 30% of our total export basket of 440 billion, which itself is roughly 15% of total GDP in Dollars.

So we are already a significant exporting power, provided we don’t let China harm our exporters anymore than it already has. Exporting 15% of your GDP, which is currently $2.88 trillion, is not a small achievement. The escape velocity for a 10% GDP growth can be achieved by stepping up exports from 15% of GDP to 30%.

Having said that, the 15% of GDP exports, as we traders say, are already in the price. The question is, how much MORE do you need to export to get to 10% which gives a decent chance of catching up with China in order to escape being marginalized or even Balkanized by it?

For 4% additional growth, we need 20% of GDP as additional savings coming from abroad by way of FPI and FDI. To service these additional savings you would have to earn an additional 20% of GDP as exports from this investment, [over a period of time of course] which means that we must up exports by at least 20 percentage points, - over a period of time - which in turn means exports have to double from $450 billion at present, to about $900 billion per annum.

Those are the numbers. Let me summarize:

To catch up with China you need to step up GDP growth rate from 6% alpha to 10% alpha as quickly as possible.

To get the extra 4% GDP growth, at an ICOR of 5, we need to increase available savings in the economy from 30% of GDP to 50% of GDP at current levels.

All of the above incremental savings, 20% of GDP, or some $600 billion must come through FDI or FPI, since domestic sources have been exhausted by Government borrowings + local investment demand. For scale & perspective, note existing FDI + FPI barely touch $100 billion a year.

The scale of foreign investment we need dwarfs what we talk about, Like 51% equity in insurance, or 50% in banks or 74% in defense related industries. All these are chicken feed compared to what we need. And this won’t happen by celebrating a “Yoga Day” once a year, and asking to be appointed VishwaGuru to the world and collect a rent for it. The world pays little Guru Dakishina to deluded VishwaGurus. The world knows and understands our economy, and our need, better than we do. It is just that they too polite to say to our face that we missed the bus long ago. And risk losing our seat on the next bus as well to our neighbors, because of misguided policies policies.

So in a nut-shell, we need 4% of GDP as incremental growth per annum, and this means we must double our exports from $450 billion to 900 billion annually, for which we need something like $600 billion in additional FDI + FPI over next 2 to 3 years.

That is the true economic meaning of the Kautilyan imperative for the Indian economy: To grow our economy at 10% plus per annum with 900 billion in exports.

Where is the credible foreign policy to achieve this objective? Where is the credible national security doctrine to make this feasible? Who are our friends, who are our foes in this endeavor? Who should we partner with in this venture, and at what terms? Where do we begin to build initial credibility for others to join the bandwagon? Who do we ally with? What is price of such alignment? What hard choices do we need to make?

These things are the nuts and bolts of security and foreign policy; and not harebrained boilerplate like the following that our erudite EAM spouts at every fleeting opportunity.

“This is a time for us to engage America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play, draw neighbors in, extend the neighborhood and expand traditional constituencies of support.”

- Jaishankar, S.

I dare say the above is more poetic prayer than policy, but hardly commands any respect even as boilerplate. Which is why I think he is a bigger disaster than Modi himself.

Reverting to the connection among economics, strategy, and security policies, at the core of our strategy, we need to understand labour arbitrage, in a fair amount of detail and depth. It is a difficult topic conceptually, as all arbitrage is by nature counter-intuitive, but once understood, the concept is easy to apply.

So I will defer that discussion to another article, and after that revert back to my original topic, which was and is: “how can we break free of Chinese containment policies for us?”

Meanwhile bear in mind the Kautilyan imperative: Add 4 percentage points to our alpha GDP growth, by doubling exports from $450 billion to $900 billion, for which we need $600 billion [annually] in FDI over the next 3 to 5 years. Mind you, this is eminently doable. And so should be done. Without this, we will keep sinking to the bottom of the global heap in prosperity, power & prestige.

It is simply said that double the export and the country would achieve everything through DGP growth. How to double the export? If it is so easy why the governments since indelendence had failed? India is a democracy. So it is very difficult to compete with China which controls everything including the labour.

Brillant essay, thorough research, and impressive expertise. Respect.